Dearborn & Inkster

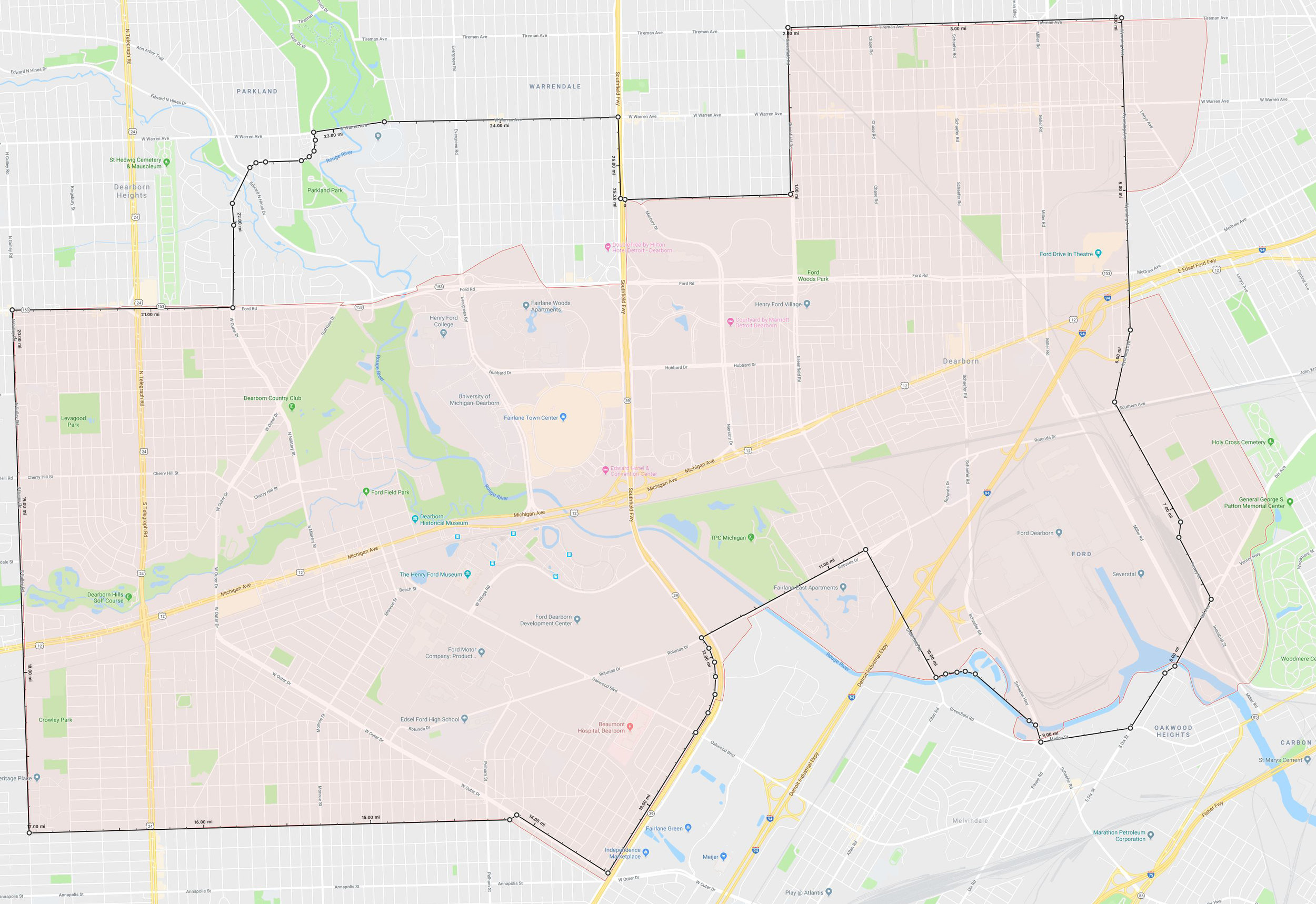

Dearborn as a white settlement started off as a stagecoach stop between Detroit and Chicago; when Michigan was still in the business of protecting itself as a frontier, Dearborn was also the site of a military arsenal which provided storage and repair of weapons. What is now Inkster was settled later and incorporated as a village in 1926. Dearborn and Inkster are linked by the legacy of Henry Ford, but are in themselves also notable.

Dearborn is dominated by Ford Motor Company and its related businesses. Henry Ford grew up in Dearborn. He moved his company’s operations there out of Detroit soon after he founded the company in 1903, and now the Ford world headquarters is located in Dearborn, along with the River Rouge plant and the Henry Ford Museum. At one point, Ford owned 25% of all land in Dearborn.

“… settler colonial and suburban forms share a conception of freedom as the ability to move away. Henry Ford encapsulated this approach when he famously proclaimed in 1922: ‘we shall solve the city problem by leaving the city.’... if the automobile made suburbia possible, the car itself constituted a re-enactment of settler migrations: it was to contain a cohesive family unit and should have had a man at the wheel.

— Lorenzo Veracini

Henry Ford had a paternalistic approach to his workers. He instituted an Americanization program for white European immigrant workers, which partly consisted of mandatory English language classes and home inspections from company “sociologists.” Ford was one of the only auto industry employers willing to hire African Americans in the early 1900s, but he soon segregated them into the “3Ds” — dirty, dangerous and demeaning jobs.

“In return for opening up jobs to African Americans, Ford expected loyalty and allegiance from black workers and their families to bolster his defense against the threat of unionism…. Given the lack of opportunity for black men elsewhere in Detroit, why wouldn't black Ford workers be loyal? Besides, Ford demanded loyalty. The price for high wages and access to jobs included surveillance of one's personal habits and beliefs and manipulation of black institutions, all part of Ford's overbearing paternalism.”

— Beth Tompkins Bates

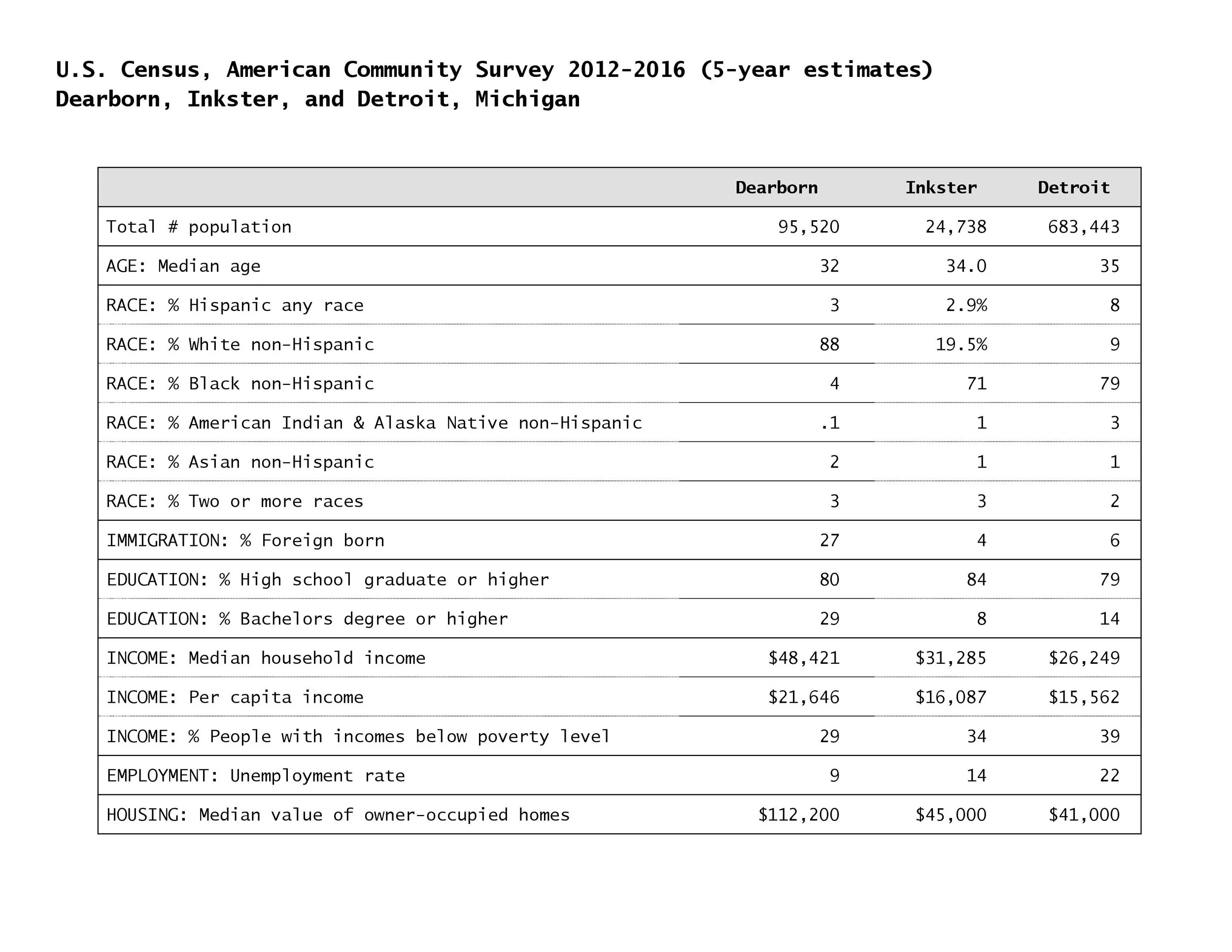

Since racial covenants and other forms of housing discrimination kept African Americans out of Dearborn, they lived in worker housing constructed next door in Inkster, which is still predominantly black today. In fact, it's 75% African American, with a median household income of about $30,000 and 45% poverty rate. Dearborn, on the other hand, is 4% African American (yes, four percent), with a median household income of $47,000 and 22% poverty rate. These differences are clearly reflected in the landscape.

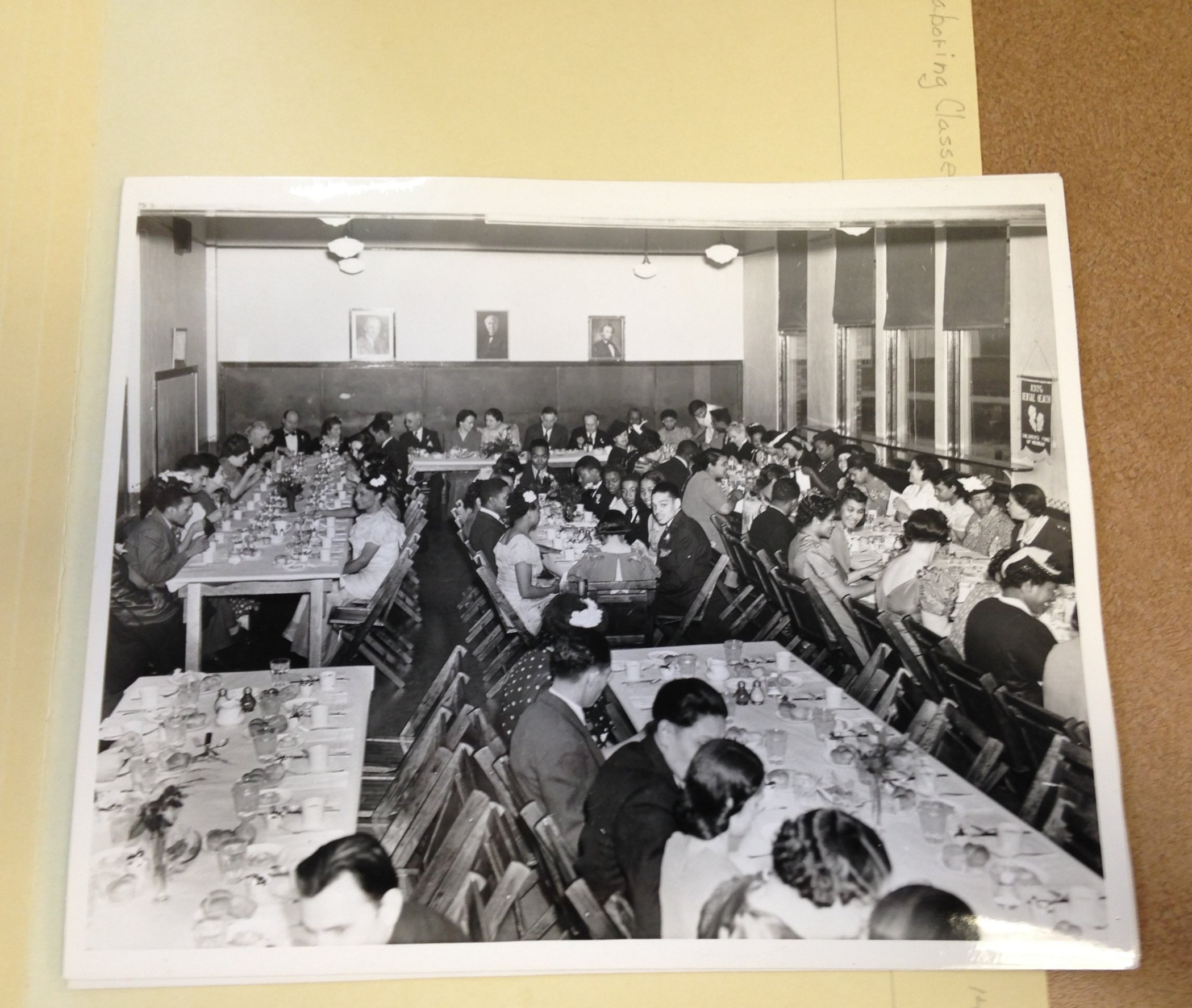

Henry Ford’s most famous contribution to Inkster happened during the Depression, when he decided to provide aid on a large scale to the residents of Inkster.

“The Inkster Project reveals the power of public relations. Good publicity about Inkster repaired Ford’s tarnished image nationally, casting him as the benevolent caretaker of black Detroit…. More than a welfare program, Ford’s loans were tied to rehabilitating morals and manners as well as material well-being. It was an effort to remake the black community from the foundation up, a clean sweep of bad debt the members of the community had incurred and the bad habits they were practicing. …

“Yet loss of privacy was part of the cost black families bore to get benefits from a system requiring house visits to evaluate finances, housekeeping practices, and consumption habits. Another cost was self-determination. The Ford plan for Inkster was not open to negotiation. In fact, when residents tried to assert their wishes and vision for repairs and reconstruction of their houses, they were reminded that there was only one way to repair and reconstruct the housing stock: Ford dictated all the terms of the relationship.”

— Beth Tompkins Bates

Dearborn had one the most outspoken advocates for segregation and racism in the north, Orville Hubbard, who served as mayor of Dearborn for 36 years from 1942 to 1978. The town motto, “Keep Dearborn Clean,” was widely interpreted as “Keep Dearborn White.” He was tried for conspiracy in mob vandalism to the home of a white man rumored to have sold his house to an African American, but was acquitted.

“Whites’ ideas about race and their preoccupation with property were relational and mutually constitutive. The political, demographic, and material conditions of postwar growth encouraged whites to view homeownership and suburban neighborhoods in racial terms — specifically, as a prerogative of white people. Conversely, whites’ ideas about race were constantly mediated by their investment, simultaneously financial and emotional, in widely held assumptions about the prerogatives of homeowners. The result was a justification for residential segregation that relied almost exclusively on the language of land-use economics and suburban autonomy. ...

“The vast majority of Dearborn residents endorsed segregation and treated it as a practical matter, driven solely by market considerations. They openly called for racial exclusion, while insisting that it was not necessarily ‘about race.’”

— David M.P. Freund

Ironically, Dearborn is now home to one of the largest communities of Arab Americans in the U.S. The roots of the community lay with the immigration of Lebanese and Syrians in the early 1900s, many of whom worked for Ford and other auto companies. Subsequent waves of newcomers have arrived since then, most recently as refugees fleeing wars in Lebanon and Iraq.

“Detroit and its suburbs are home to a large, diverse population of Arab immigrants and their descendants. Population estimates, always controversial, are routinely inflated by Arab American activists — who claim numbers as high as 400,000 for the Detroit community — but even sober demographic calculations suggest a population of roughly 125,000 people. Arabs in Detroit tend to reside in the suburbs. The most visible concentration is in Dearborn, where Lebanese, Yemenis, Iraqis and Palestinians, almost all of them Muslim, have built a vibrant terrain of mosques, ethnic business districts, social service agencies, political action committees, village clubs, and neighborhood associations. …

“It is hard now to portray Arab Detroit outside the framework provided by the attacks of September 11, 2001…. As the Bush administration's War on Terror expands, however, Arab Detroit's rich history of domestic integration and transnational connection is being truncated, questioned, repoliticized, Americanized, and selectively erased. This radical transformation is rooted in anxiety about boundaries: Arabs and Muslims are clearly 'in Detroit,' with 'us,' but their hearts might still be 'over there,' with 'them.'”

— Sally Howell and Andrew Shryock

Sources:

Barrow, Heather B. Henry Ford's Plan for the American Suburb: Dearborn and Detroit. Northern Illinois University Press, 2015.

Bates, Beth Tompkins. Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford. University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Howell, Sally and Andrew Shryock, “Cracking Down on Diaspora: Arab Detroit and America's War on Terror.” In Arab Detroit 9/11: Life in the Terror Decade. Edited by Nabeel Abraham, Sally Howell, and Andrew Shryock. 2011.

Freund, David M. P. Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Lindsey, Howard O'Dell. Fields to Fords, feds to franchise: African American empowerment in Inkster, Michigan. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Michigan, 1993.

Thomas, Richard W. Life for Us Is What We Make It: Building Black Community in Detroit, 1915–1945. Indiana University Press, 1992.

Veracini, Lorenzo. “Suburbia, settler colonialism and the world turned inside out.” Housing, Theory and Society, 29(4), 339–357. 2012.