100 Miles in Chicagoland (2019)

During October 2019, I conducted a series of durational walking performances that witness the histories of settler colonialism, racial segregation, and class exploitation that shape the Chicago region to this day.

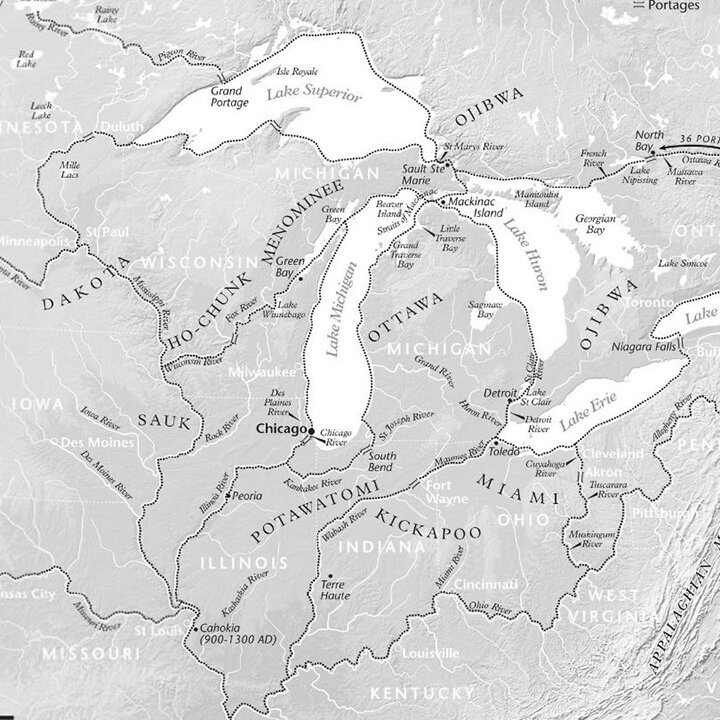

The walks traced the path of trails created by Indigenous peoples for complex networks of trade and travel long before settlers came. Today’s roads cut through neighborhoods with distinctive characters of race and class, produced by decades of deliberate policies around housing, transportation, land use, economic development, immigration, and the environment.

While walking, I wore a traditional Korean dress made from denim, an all-American fabric imbued with the history of slavery in cotton and indigo, to mark my various identities as a Korean female, an immigrant, a settler, and an “American.”

Five walks of 20 miles each were conducted —

Wednesday October 2: Vincennes

Wednesday October 9: Ogden/Plainfield

Wednesday October 16: Lake

Wednesday October 23: Elston/Milwaukee

Wednesday October 30: Clark/Ridge/Green Bay

Presented as part of Terrain Biennial 2019.

Selected Notes & Research

Parts of this text have been edited and printed as a chapter in Ways of Walking, ed. Ann de Forest (New Door Books, 2022) (see link here). The chapter is available here.

Vincennes

I start each walk at the piece of land six miles square at the mouth of the Chicago River. Today it’s still dark outside when I start, and the air is damp and drizzly. I’m walking south on the Native path renamed by settlers as the Vincennes Trail. In 1914, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians sued the city of Chicago and others for the land east of this path. In the Treaty of 1833, they had given up their lands up to the shore of Lake Michigan. But the city had since created land beyond the shore, landfill that was now Streeterville, Millennium Park, the Art Institute, Grant Park, and other valuable lakefront property. And that land, the Potawatomi said, they had not ceded. The Supreme Court ruled against the tribe, saying that while they may have had a right to occupy the land, they had since abandoned it, and, “for more than half a century no pretense of such occupancy has been made by the tribe.” An odd argument, seeing that the land had been underneath the lake, and that the Potawatomi had been forced to leave Chicago by the 1833 treaty. Walking along Michigan Avenue in the heart of downtown shopping, culture, and tourism puts me almost precisely on the original lakefront. I imagine water lapping my feet on the left, sandy dunes on my right, and the broken type of a Supreme Court judgment rolling out on the sidewalk before me.

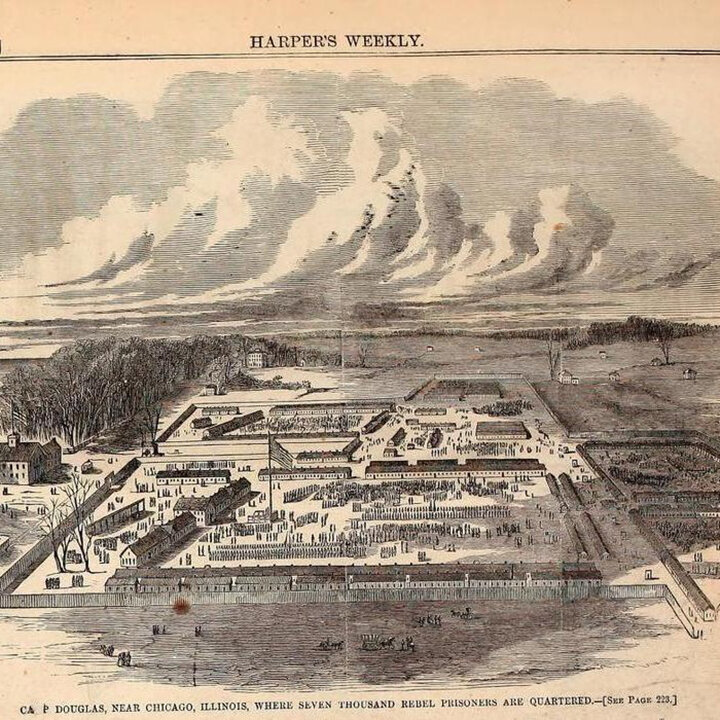

The ghosts of war are everywhere. These apartment buildings dot a landscaped complex across the street from where I’m walking, the product of contested urban renewal in the 1960s. One hundred years before that, this was the location of a Civil War Union Army camp that held 12,000 Confederate prisoners-of-war. Over a third of them died from poor conditions. Many are buried in a mass grave marked by a 30-foot monument at Oak Woods Cemetery in Hyde Park, one of the first cemeteries in the city, where prominent Black Chicagoans like Harold Washington and Ida B. Wells are also buried. Activists have called for removal of this memorial to Confederate soldiers located in the predominantly Black south side of Chicago. The ghosts roam freely in the streets, watching to see if, how, and what we remember.

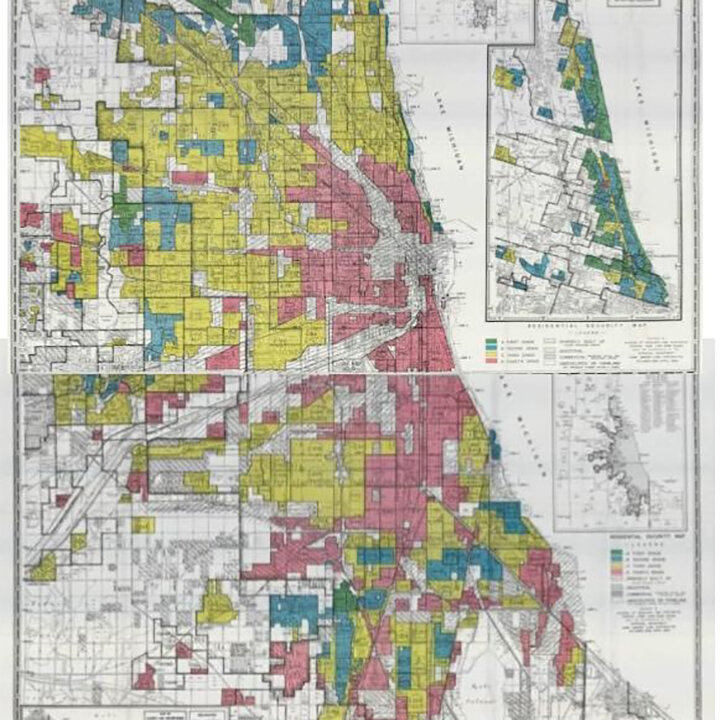

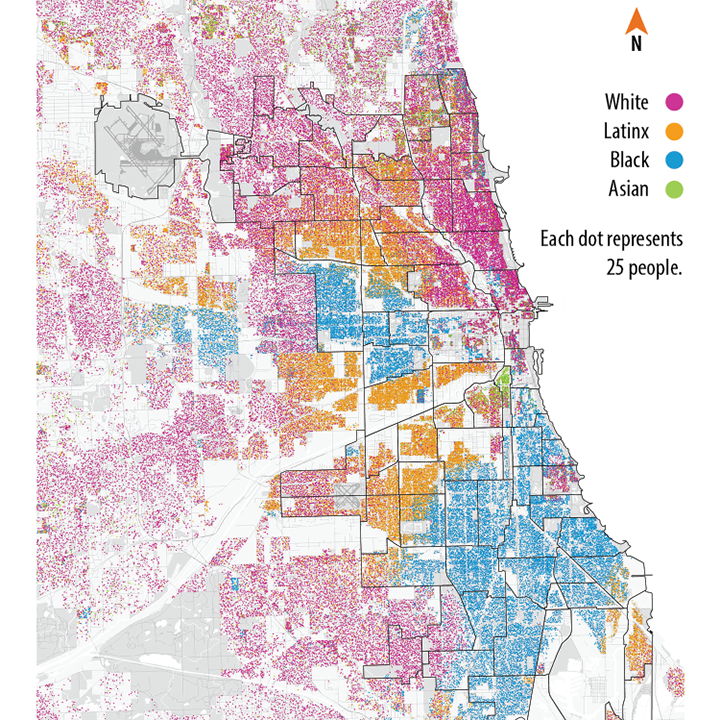

Here’s another monument, one to the Great Migration by Alison Saar. It’s one of the few public artworks in Chicago made by Black women. From 1915 to 1970, the number of African Americans in Chicago grew from 15,000 to one million, less than 2% to one-third of the whole city. Drawn by networks of family and friends, recruited by factories that needed labor, recent descendants of kidnapped and enslaved Africans thronged to the big city, only to be confined to the “Black Belt.” As the numbers of newcomers stretched the limits of their containment, the question as stated by St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Jr. in their iconic Black Metropolis was: “Where would the black masses, still bearing the mark of the plantation upon them, find a place to live?" Where indeed? Repeated, vicious, multiply reinforcing policies and practices excluded and restricted African Americans into still existing, very evident patterns of hyper-segregation and impoverishment. The concept of the “underclass” was developed here in Chicago. Riots, violence, restrictive covenants, redlining, racial steering, urban renewal, public housing, transportation policies, land use policies, redevelopment -- all the mechanisms possible have been used here in Chicago to confine movement, deny dignity, limit possibilities.

It’s drizzling again as I walk past empty lots. The mist blurs the ghost of the Robert Taylor Homes that used to stand on these fields. Completed in 1962, the infamous public housing project housed 27,000 people at its height, 20,000 of them children. Ironically, it was named after Robert Taylor, the first African American chair of the Chicago Housing Authority board, who quit when the City Council opposed scattered site public housing in order to preserve racial segregation in the city. The housing project was demolished in 2007. Only a fraction of the housing since rebuilt on the site is affordable for low income families. In a logic where land only has value in its use, does the emptying of land here reflect the value placed on the people who used to live here?

Ogden & Plainfield: Southwest Plank Road

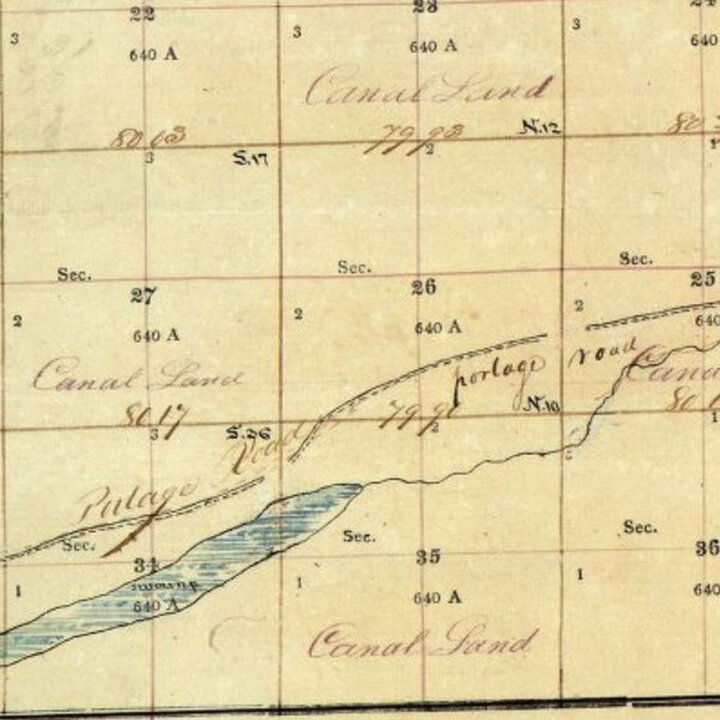

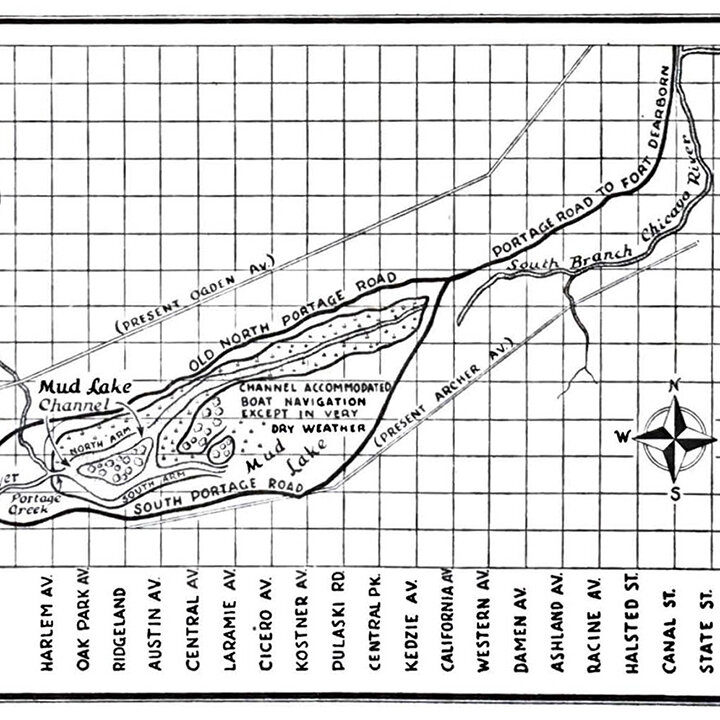

The land was intended for a canal, a dream of Europeans and Americans from the moment they first learned of this portage between the Des Plaines and Chicago Rivers. Used by Native people as a transportation hub between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River, a location this strategic was irresistible for settlers. The U.S. did indeed build a canal, with money from selling the land around it. The portage itself is gone, but its location is now a national historic site, whose website proclaims: “The Chicago Portage is the birthplace of Chicago. The Chicago Portage National Historic Site is the only major remnant of the discovery and settlement of Chicago…. The late Tribune columnist John Husar, after touring the site called it: ‘Our sacred ground’. It is certainly Chicago’s ‘Plymouth Rock’.” The 1493 Doctrine of Discovery doesn’t hide itself anywhere - its logic underlies all of settler colonialism, feeling as natural as the air we breathe and the ground we walk on.

I live 8 miles north of this intersection. I’m in the North Lawndale neighborhood, featured by Ta-Nehisi Coates as a case study of the legacy (and ongoing presence) of systemic racism against Black people. “We believe white dominance to be a fact of the inert past, a delinquent debt that can be made to disappear if only we don’t look…. But still we are haunted. It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear. The effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us.” Coates talks about the plunder of Black bodies, Black labor, and Black families as the foundation for white democracy. He talks about segregation, redlining, and the Contract Buyers League, an extraordinary episode of organizing. And then he compares slave ownership to homeownership, that it was equally aspirational in its time, and the idea of ending slavery was equally unthinkable. He says: “Imagine what would happen if a president today came out in favor of taking all American homes from their owners: the reaction might well be violent.” And I wonder: how did we start thinking that ownership of anything was a right? How do we unhitch our aspirations from those created through violence? How do we dispossess the American dream, predicated on land as property?

So much transportation on today’s sunny walk. Across the street for blocks and blocks is the Cicero Intermodal Terminal for BNSF, the largest freight railroad company in North America. “Intermodal” means containers get moved between trucks, trains and ships -- the canal, railroad tracks, and the I-55 highway all parallel each other here. In 2014, the EPA found that this terminal created high levels of diesel pollution that swept over the surrounding residential areas, where I’m walking. Exposure to diesel exhaust has been linked to asthma, cancer, heart attacks, brain damage, and premature death. Of the 340,000 people who live within a half-mile of an intermodal terminal in the Chicago region, more than 80% are Latinx or African American. Such consistency in who is deemed expendable: what land, whose communities. Indeed, these areas are called “sacrifice zones.” After all, someone has to be sacrificed for the American Dream, right?

I was unprepared for this twice over. The first time was when I researched this walk and came across this sentence in Scharf’s notes: “This trail was the one used by the Pottawatomie Indians in their departure from Chicago, in 1835.” The second time was when I saw this marker, at the entrance to a subdivision in Western Springs: “Last Camp Site of the POTAWATOMIE INDIANS in Cook County 1835; Erected by LaGrange Illinois Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution MAY 15th 1930.” According to the Western Springs Historical Society, Potawatomi people left after the 1833 treaty in groups. The last group, about 70 people, departed Chicago in Fall 1835, and slept that first night of travel at the farm of Joseph Vial. He had come from New York two years before and bought 170 acres of land from the U.S. government, which had just acquired it through the 1833 treaty. Vial paid the government $1.25 per acre, the equivalent of $33 today. The subdivision now on that land is still building and selling new homes, priced in the $600,000s. This placid suburban scene denies that land was taken, people displaced, and resources extracted to make itself possible. How do we see what has deliberately and violently been made unseen?

Lake

The theme today is transportation. I’m walking parallel to I-290, known as the Eisenhower Expressway, one of the main arteries running through downtown Chicago. Built in stages during the 1950s, it was part of a new superhighway system designed to relieve traffic in Chicago but conveniently deployed to eliminate “blight”, code word for working class neighborhoods and communities of color. Highways take up enormous parcels of land. The Eisenhower displaced about 13,000 people and 400 businesses, including in the Near West Side neighborhood which was almost 40% African American. Oak Park, the first suburb west of Chicago, fought the highway, and was successful in getting center lane ramps which take less land than clover-leaf ramps.

El trains clatter above me; on either side is miles of empty lots and vacant industrial buildings. Research confirms what I see: Industry has been leaving the West Side for decades, going to the suburbs where there’s more land for cheaper, with taxpayer-funded incentives and less environmental cleanup. The result? Less than 15% of manufacturing jobs remain in the city from fifty years ago. Which is partly why the unemployment rate for African Americans in the city is twice the regional average. Which might explain why they’re leaving: African Americans used to be the largest racial group in Chicago, numbering more than one million in 2010, but one out of every four have since left. While some moved to the suburbs, many have left the whole region, a reverse Great Migration to places like Atlanta and Houston. Everything conspired to push people out. Capitalism eats land and people, and moves on. What will we become without our Black neighbors? What happens when it’s our turn to get eaten up by capitalism?

Elston & Milwaukee: Northwest Plank Road

Today I’m walking northwest, where white people live. Construction is clearly the theme: construction = money = investment, in the form of new office buildings, condos, libraries, and street improvements. I pass the outer edge of Lincoln Yards; the city approved a $1.3 billion tax increment financing district for this $6 billion project. In exchange for what? Protestors question whether the development will create enough affordable housing, whether it will simply perpetuate racial segregation in the city. A 2019 report says that home mortgages, small business loans, and commercial real estate investment disproportionately benefit white and middle/upper income neighborhoods in Chicago. Majority-white neighborhoods receive 2.6 times more than majority-Latino neighborhoods and 4.6 times more per household as majority-Black neighborhoods. That’s $22,476/year per household in the majority-white neighborhood compared with $8,569 in majority-Latino neighborhoods and just $4,927 in majority-Black neighborhoods. You can see that money (and lack of it) in the streets and buildings. It’s quite evident on these walks.

This forest preserve, a golf course, a nearby road, and the entire neighborhood are named after Sauganash, also known as Billy Caldwell. Born to a Mohawk mother and English father, he came to Chicago in the late 1700s and married into the Potawatomi tribe. For his role in negotiating the Treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1829, Caldwell received 1,600 acres of land. He started selling it off a few years later, and then was forced west with other Potawatomi after the 1833 Treaty. Almost forty years later, a man came forward as Caldwell’s son to ask about the land. The Bureau of Indian Affairs told him that a portion of the plot, 160 acres, had been sold without permission of the U.S. president, a condition regularly built into treaties ostensibly to protect Native people. The land remained unrecovered, and it was sold to the Cook County Forest Preserve in 1917 and 1922. Technically, Caldwell’s descendants might still be able to make a claim to this piece of land. Stories like this lay bare the colonized status of land, pulling the fact of occupation into the present day. Those of us who grew up in Illinois, a state that lacks a single federally recognized tribe, aren’t used to the idea of Native people actually living on their ancestral land.

Green Bay

It’s my final walk. It’s drizzling again, a freezing rain. I head north across the bridge, where there’s a bust of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. We read about him in school, the first non-Native settler, founder of modern Chicago, its first immigrant, a visionary and entrepreneur. Of African descent, he may have been born in Haiti or Canada, and was a fur trader when he came to the Chicago area. He married a Potawatomi woman named Kitihawa, established a farm and trading post right near this spot, and moved away in 1800 to St. Charles. The farm was eventually bought by John Kinzie, a Canadian and leading figure in early settler Chicago. African Americans in Chicago protested for many years about the lack of recognition of Du Sable, a black man, especially compared to the number of places named after Kinzie, a white man. Next year is the 100th anniversary of this bridge, but it was only named after Du Sable nine years ago after a campaign by African Americans for recognition.

As uncertain as some of the facts are about Du Sable’s life, almost nothing is known about his wife Kitihawa. It’s probable that his marriage into the Potawatomi networks of his wife is what enabled his success in business. They had two children, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable Jr., and Suzanne. Where are their descendants now, the mixed Black/Native/French inheritors of Chicago’s founding myths? How can we know about Kitihawa, with no records languishing in archives or stories circulating in communities? How did she grow up, what kind of person was she, what did she think about or like to do? And what happens now, in the present, when we add a bust of Du Sable on the Magnificent Mile, or campaign to re-name Lake Shore Drive after Kitihawa? What do we proclaim when we celebrate the founding of anything on this continent, and what does it mean if those people are black and Native?

I’m walking along the Magnificent Mile, home to upscale shopping and now the world’s largest Starbucks. According to Dominic Pacyga and Ellen Skerrett, this shopping mecca was the result of a domino chain of retail white flight in Chicago. In the 1950s, after restrictive covenants were outlawed, African Americans started to move out of the so-called Black Belt into other parts of the south and west side. Retailers in those neighborhoods preferred to leave rather than serve their new black customers, so with few options for shopping, African Americans began coming to State Street downtown. Higher priced retailers there pulled up their stakes and moved to this stretch of Michigan Avenue, boosted by city redevelopment financing and a strategic marketing campaign. Racism’s distaste of proximity to black bodies extends to shopping, even within capitalism.

My cousin used to live in this complex. I once dated someone who lived here too. This place is the result of urban renewal in the 1960s. Previously the neighborhood was known as La Clark, home of the first sizeable community of Puerto Ricans in Chicago. As working class people of color started moving closer to the tony Gold Coast, the city decided that the land was blighted. It demolished the entire neighborhood, moved people out, and financed a $6.4 million complex of high rise apartments and low rise townhouses for middle and upper income professionals. From 1950-1966, Chicago displaced over 80,000 people through urban renewal, the most per capita in the nation. Forced to move to Lincoln Park and Humboldt Park, displaced Puerto Rican youth fought back, forming the Young Lords Party and a national movement for self-determination. No marker, no monument alerts pedestrians to this history. It requires organized resistance to even document stories of resistance.

I’m looking for a place to get dry when I reach Wrigley Field. In 1970, Carol Warrington (Menominee) and her children were evicted from their apartment behind Wrigley Field. She had withheld rent for two months to protest the poor conditions of her apartment. Native organizers rallied around her eviction, and camped at Waveland and Seminary for three months to protest substandard housing for Native Americans. Led by Mike Chosa (Ojibway), this group became the Chicago Indian Village and went on to stage encampments for two years, occupying buildings and federal properties to bring attention to housing needs for Native Americans. At one point, they started demanding land — the organizers knew they would never get the land, but thought this would make their demand for better housing seem like “smaller potatoes.” Most Native people living in Chicago had come as a result of the relocation program of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs in the 1950s. The program was one of the BIA’s termination policies designed to assimilate Native people, which also included ending federal recognition for tribes. The BIA commissioner championing this effort had previously headed the War Relocation Authority, in charge of imprisoning Japanese Americans into internment camps. Sometimes the connections are right there, you don’t even have to make it up or stretch at all.

My family moved to Wilmette after my first year of high school. We were on the immigrant upward mobility track, and my mother wanted us to go to “better” schools. Only recently did I learn that this suburb is named after a French Canadian settler, Antoine Ouilmette, and is located on the reserve deeded to his Potawatomi wife, Archange Chevalier. Antoine helped to negotiate the 1829 treaty; in return Archange got 1,280 acres in what is now Wilmette and Evanston. The Ouilmettes lived there from the 1820s until 1840, when they moved to join their Potawatomi kin in Iowa following the removal of the tribe. Archange died right afterwards, at the age of seventy-six, and her husband died the next year. Their children sold the land in the following decade, and a land syndicate was formed by white settlers to promote residential development. In the 1920s, the town annexed neighboring Gross Point, and built a 170-acre development there named Indian Hill Estates. Wilmette is now one of the ten wealthiest towns in Illinois.

I’m done, at the end of my final walk. I’m in Glencoe, the richest place in Illinois, 10th richest in the U.S., with an average household income of $340,000. Winnetka, just south of that, is the second richest in the state. The median home value in these areas is over $1 million, which means half of all the houses are worth more than that. These suburbs are 90% white. In 2013, white families had 13 times the amount of wealth as Black families. The wealth gap is often attributed to the ongoing legacy of slavery and what Ta-Nehisi Coates defines as theft, policies that have prevented Black people in the U.S. from accumulating intergenerational wealth. For most families, of any color, wealth is acquired through owning property, specifically a home. In fact, it is the American Dream. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz says: “Once in the hands of settlers, the land itself was no longer sacred, as it had been for the Indigenous. Rather, it was private property, a commodity to be acquired and sold -- every man a possible king, or at least wealthy. Later, when Anglo-Americans had occupied the continent and urbanized much of it, this quest for land and the sanctity of private property were reduced to a lot with a house on it …” Walking through these neighborhoods of houses that average 3,800 square feet, I wonder about how one defines wealth in the context of racism and settler colonialism. What is true wealth?